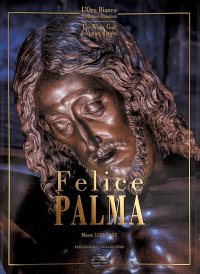

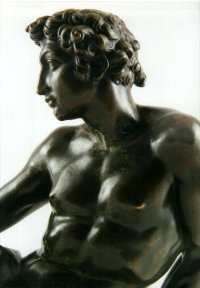

Felice Palma. Massa 1583-1625. Collezione / Collection.

Texts by Andrei Cristina, Ciarlo Nicola, Federici Fabrizio, Claudio Casini and Sara Ragni.

Italian and English Text.

Pontedera, 2024; bound in a case, pp. 289, b/w and col. ill., b/w and col. plates, cm 24,5x34.

(L'Oro Bianco. Straordinari Dimenticati. The White Gold Forgotten Masters).

cover price: € 160.00

|

Books included in the offer:

Felice Palma. Massa 1583-1625. Collezione / Collection.

Texts by Andrei Cristina, Ciarlo Nicola, Federici Fabrizio, Claudio Casini and Sara Ragni.

Italian and English Text.

Pontedera, 2024; bound in a case, pp. 289, b/w and col. ill., b/w and col. plates, cm 24,5x34.

(L'Oro Bianco. Straordinari Dimenticati. The White Gold Forgotten Masters).

FREE (cover price: € 160.00)

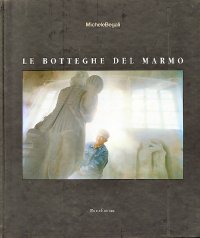

Le botteghe del marmo

Italian and English Text.

Ospedaletto, 1992; bound, pp. 153, 10 b/w ill., 60 col. ill., cm 24x29.

(Immagine).

FREE (cover price: € 34.49)

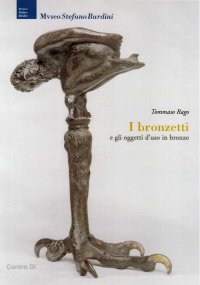

Museo Stefano Bardini. I Bronzetti e gli Oggetti d'Uso in Bronzo

Edited by Nesi A.

Firenze, 2009; paperback, pp. 191, 102 b/w ill., 7 col. ill., cm 17x24,5.

(Museo Stefano Bardini).

FREE (cover price: € 30.00)

Bronzetti e Rilievi dal XV al XVIII Secolo

Bologna, 2015; 2 vols., bound in a case, pp. 729, ill., col. plates, cm 21,5x30,5.

FREE (cover price: € 90.00)

The latin inscriptions of Medici Florence. Piety and propaganda, civic pride and the classical past. Nuova ediz

Kragelund Patrick

Quasar Riviste

New edition.

Roma, 2021; paperback, pp. 364, b/w and col. ill., cm 15x18.

(Analecta Romana Instituti Danici. Supplementa. 55).

series: Analecta Romana Instituti Danici. Supplementa

ISBN: 88-5491-115-1 - EAN13: 9788854911154

Subject: Essays on Ancient Times,Historical Essays

Period: 0-1000 (0-XI) Ancient World,1000-1400 (XII-XIV) Middle Ages,1400-1800 (XV-XVIII) Renaissance,1800-1960 (XIX-XX) Modern Period

Places: Florence,Italy,Tuscany

Languages:

Weight: 1.747 kg

Among the early highlights are inscriptions commemorating the father of Dante's Beatrice and the building of Ponte Vecchio, of the Bargello and the Duomo. The book opens new perspectives by unravelling how the humanist study of classical epigraphy from the 1430s onwards made a lasting impact on the composition of Florentine inscriptions. This is a hitherto little acknowledged aspect of the so-called civic humanism. While moving away from a framework based upon Scripture and Christian values, civic humanism looked to ancient Rome for inspiration and models.

Another focus is the way the rise to power of the Medici is mirrored in centralised efforts to give official epigraphy the suitably Augustan and imperial (as opposed to republican) formats. From 1537 onwards, Cosimo, the second Duke and, eventually, the first Grand Duke, literally inscribed what was now his city of residence, its walls, bridges, churches, mercati, squares and monuments - and this in a manner underlining his monarchical ambitions. When the decline of the Grand Duchy set in, this was mirrored in a decline of the dynasty's epigraphical self-promotion, memorials in the end often focusing on past glories.

What survived Florence's transition from merchant republic to monarchy was the pervasive and highly patriotic cult of uomini illustri. Monuments to men of letters and art are numerous, this trend reaching its nadir with the memorials for the divine Michelangelo. In contrast, honours for the period's greatest scientist, Galilei Galileo, was at first vehemently opposed by the Church, his belated rehabilitation only taking place almost a century after the Inquisition had condemned his teachings

Simonetti Dario € 23.75

€ 25.00 -5 %